Note: If you are impatient, see my newer post on an actual solution to the bay bridges challenge.

I recently came across the Bay Bridges Challenge, over at CodeEval. The challenge is to pick the largest set of bridges for construction, such that no two bridges cross or intersect.

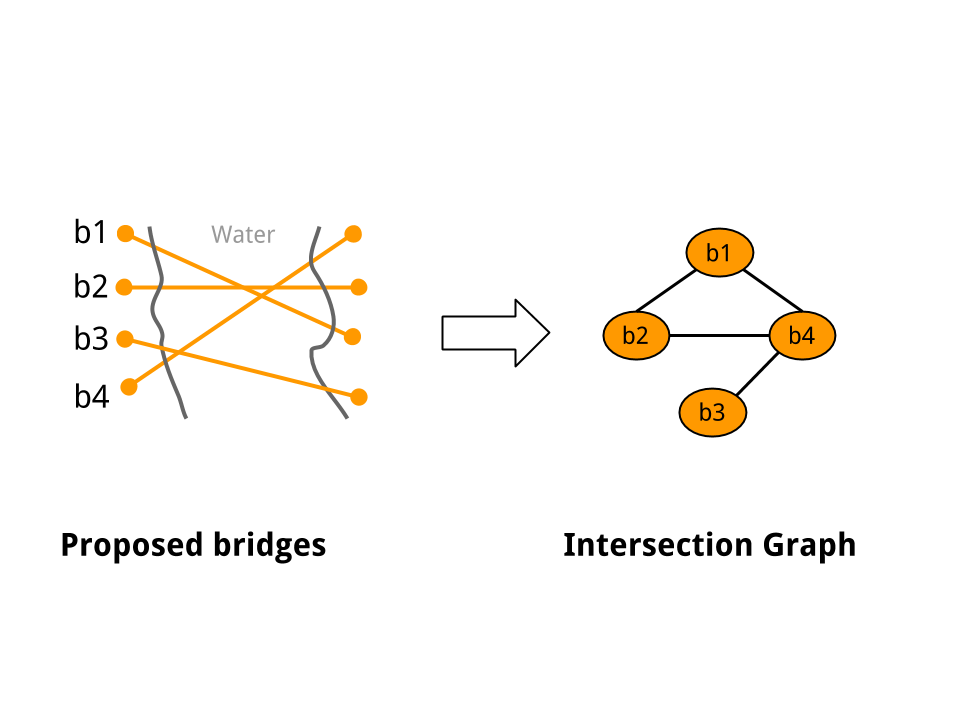

My first instinct was to model this as a graph problem. Suppose we construct an intersection graph G, as follows: create a graph node (or a vertex) corresponding to each bridge, and add an edge between two vertices u and v if and only if the corresponding bridges cross. Figure 1 below shows an example. Then, its easy to see that the original problem is equivalent to finding the minimum vertex cover on G.

Figure 1: A Sample Intersection Graph

Figure 1: A Sample Intersection Graph

It turns out that finding the minimum vertex cover is NP-hard. For this problem, it means (roughly) that we can do no better than to iterate through the power set of bridges, and pick the highest cardinality subset that is feasible (i.e., no two bridges in that subset cross). That was a bit disheartening. But it is unlikely that a run-of-the-mill coding challenge requires coming up with acceptable approximation algorithms to hard problems. Most likely, there is additional structure inherent in the problem, that can be exploited to make the problem more tractable.

Since the bridges exist in a 2-D plane (roughly), we can use the distance metric to automatically rule out large portions of the search space. For example, if a bridge does not cross any other bridge, then it is always included in every optimal solution. By eliminating such bridges from consideration, we might reduce the problem size considerably. Spatial data structures like bounding rectangles, k-d trees, or their cousins can be used to partition the set of bridges into smaller subsets, and solve many smaller, independent sub-problems (maybe even in parallel). But none of these approaches reduce the essential strength of the problem, since we are still looking at exponential worst-time solutions.

At this point, I was feeling a bit stuck. My attempts at finding additional structure in the original problem space hadn’t really helped. But going over the Wikipedia page on vertex covers, I read that a minimum vertex cover can be found in polynomial time for bipartite graphs. Finally, some progress: If the intersection graph G is bipartite (a graph’s bipartite-ness can be tested in linear time), we have an efficient solution. But it is not hard to come up with real world inputs where the intersection graph is not bipartite. For example, in Figure 1 above, the intersection graph is not actually bipartite (However, if you imagined that bridge b4 was removed from the input, the remaining graph would indeed become bipartite). So, we still don’t have a solution that always works.

As of this point, I haven’t written a line of code. My hunch is that I need to look for a solution in the original problem space: the roughly Euclidean plane on which the line segments corresponding to the bridges exist, and not in the intersection graph space.